Mao Zedong: Difference between revisions

Undo revision 41875 by 2.96.223.76 (talk) |

Rangerkid51 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (369 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[ | <br />{{Important}} | ||

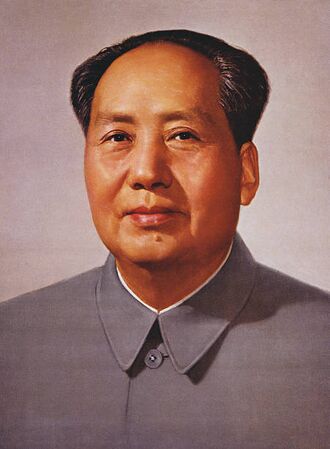

{{Quote|Politics is war without bloodshed, while | {{Villain Infobox | ||

'''Mao Zedong''' (December 26, 1893 - September 9, 1976) was the Communist Leader of the People's Republic of China and led the "Leap Forward" movement to break all traditions of Ancient | |Image = Chairman Mao.jpg | ||

|fullname = Mao Zedong | |||

|skills = Army commanding<br>Leadership<br>Propaganda<br>Manipulation | |||

|hobby = Writing poetry<br>Sailing<br>Reading | |||

|alias = Chairman Mao<br>Mao Tse-tung<br>Great Helmsman<br>The Red Sun<br>Savior of the People<br>The Red Emperor<br>Li Desheng <small>(temporary alias)</small> | |||

|occupation = Chairman of the [[Communist Party of China]] (1943 - 1976) | |||

|goals = Establish The People's Republic of China (succeeded)<br> Take over Tibet (succeeded)<br>Completely unify Taiwan (failed)<br>Destroy the United States (failed) | |||

|type of villain = Delusional Dictator | |||

|origin = Shaoshin, Hunan, Qing Empire (now Shaoshan, Hunan Province, China) | |||

|crimes = [[Mass murder]]<br>[[War crimes]]<br>Conspiracy<br>Aiding and abetting<br>[[Crimes against humanity]]<br>Human rights violations<br>[[Torture]]<br>Mass starvation<br>Mass internment<br>Mass repression<br>Destruction of religious and cultural artifacts<br>[[Genocide]]<br>[[Anti-Japanese sentiment]]<br>[[Anti-Taiwanese sentiment]]<br>[[Hate Speech]]<br>[[Ethnic cleansing]]<br>[[Misogyny]]<br>[[Xenophobia]]<br>[[Kidnapping]]<br>[[Acephobia]]<br>[[Ableism]]<br>[[Discrimination]] | |||

|name=Mao Zedong}} | |||

{{Quote|Politics is war without bloodshed, while war is politics with bloodshed.|Mao Zedong}} | |||

'''Mao Zedong '''(December 26<sup>th</sup>, 1893 - September 9<sup>th</sup>, 1976), commonly known as '''Chairman Mao''', was the Communist Leader of the People's Republic of China from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976 and led the "Great Leap Forward" movement to break all traditions of Ancient China. His Cultural Revolution all but destroyed China's heritage. | |||

A major player in the [[Cold War]], Mao is considered to be a pioneer of communism alongside [[Joseph Stalin]], developing his own brand of communism known as Maoism (also known as Mao Zedong Thought). He also pioneered the [[People's War]] strategy commonly used by many Communists in armed struggle. | |||

Mao | Although many of Mao's campaigns, most notably The Great Leap Forward lead to the death of millions, many historians have pointed out that many of the deaths under Mao's regime were unintentional unlike many of the deaths under [[Nazi Party|Nazi Germany]] or the Soviet Union. He is widely considered one of the most polarizing and controversial figures in recent history, many regard him as a capable and necessary leader who improved health care, women's rights and industrialized China and see many of his campaigns as taking significant risks, while in contrast his critics have drawn comparisons between him and dictators such as [[Joseph Stalin]] and [[Adolf Hitler]] due to his radically destructive and neglectful polices against his own people. Some estimates say that between 30 million-80 million people in total died under his regime and for this reason he is considered by some historians to be ''the'' most brutal dictator in history. | ||

== Biography == | |||

=== Early life === | |||

Mao was born in the village of Shaoshan in Hunan province, the son of a former peasant who had become affluent as a farmer and grain dealer. He grew up in an environment in which education was valued only as training for keeping records and accounts. From the age of eight he attended his native village’s primary school, where he acquired a basic knowledge of the <em>Wujing</em> (Confucian Classics). At 13 he was forced to begin working full-time on his family’s farm. Rebelling against paternal authority (which included an arranged marriage that was forced on him and that he never acknowledged or consummated), Mao left his family to study at a higher primary school in a neighbouring county and then at a secondary school in the provincial capital, Changsha. There he came in contact with new ideas from the West, as formulated by such political and cultural reformers as Liang Qichao and the Nationalist revolutionary Sun Yat-sen. Scarcely had he begun studying revolutionary ideas when a real revolution took place before his very eyes. On October 10, 1911, fighting against the Qing dynastybroke out in Wuchang, and within two weeks the revolt had spread to Changsha. | |||

Enlisting in a unit of the revolutionary army in Hunan, Mao spent six months as a soldier. While he probably had not yet clearly grasped the idea that, as he later put it, “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” his first brief military experience at least confirmed his boyhood admiration of military leaders and exploits. In primary school days, his heroes had included not only the great warrior-emperors of the Chinese past but Napoleon I and George Washington as well. | |||

The spring of 1912 marked the birth of the new Chinese republic and the end of Mao’s military service. For a year he drifted from one thing to another, trying, in turn, a police school, a law school, and a business school; he studied history in a secondary school and then spent some months reading many of the classic works of the Western liberal tradition in the provincial library. That period of groping, rather than indicating any lack of decision in Mao’s character, was a reflection of China’s situation at the time. The abolition of the official civil service examination system in 1905 and the piecemeal introduction of Western learning in so-called modern schools had left young people in a state of uncertainty as to what type of training, Chinese or Western, could best prepare them for a career or for service to their country. | |||

Mao eventually graduated from the First Provincial Normal School in Changsha in 1918. While officially an institution of secondary level rather than of higher education, the normal school offered a high standard of instruction in Chinese history, literature, and philosophy as well as in Western ideas. While at the school, Mao also acquired his first experience in political activity by helping to establish several student organizations. The most important of those was the New People’s Study Society, founded in the winter of 1917–18, many of whose members were later to join the Communist Party. | |||

From the normal school in Changsha, Mao went to Peking University in Beijing, China’s leading intellectual center. The half year he spent there working as a librarian’s assistant was of disproportionate importance in shaping his future career, for it was then that he came under the influence of the two men who were to be the principal figures in the foundation of the CCP: Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu. Moreover, he found himself at Peking University precisely during the months leading up to the May Fourth Movement of 1919, which was to a considerable extent the fountainhead of all of the changes that were to take place in China in the ensuing half century. | |||

In a limited sense, May Fourth Movement is the name given to the student demonstrations protesting against the decision at the Paris Peace Conference to hand over former German concessions in Shandong province to Japan instead of returning them to China. But the term also evokes a period of rapid political and cultural change, beginning in 1915, that resulted in the Chinese radicals’ abandonment of Western liberalism for Marxism and Leninism as the answer to China’s problems and the subsequent founding of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. The shift from the difficult and esoteric classical written language to a far more-accessible vehicle of literary expression patterned on colloquial speech also took place during that period. At the same time, a new and very young generation moved to the centre of the political stage. To be sure, the demonstration on May 4, 1919, was launched by Chen Duxiu, but the students soon realized that they themselves were the main actors. | |||

From then onward his generation never ceased to regard itself as responsible for the country’s fate, and, indeed, its members remained in power, both in Beijing and in Taipei (Taiwan), until the 1970s. | |||

During the summer of 1919 Mao Zedong helped to establish in Changsha a variety of organizations that brought the students together with the merchants and the workers—but not yet with the peasants—in demonstrations aimed at forcing the government to oppose Japan. His writings at the time are filled with references to the “army of the red flag” throughout the world and to the victory of the Russian Revolution of 1917, but it was not until January 1921 that he was finally committed to Marxism as the philosophical basis of the revolution in China. | |||

=== Role in wars and political parties === | |||

The | ==== Mao And The Chinese Communist Party ==== | ||

In September 1920 Mao became principal of the Lin Changsha primary school, and in October he organized a branch of the Socialist Youth League there. That winter he married Yang Kaihui, the daughter of his former ethics teacher. In July 1921 he attended the First Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, together with representatives from the other communist groups in China and two delegates from the Moscow-based Comintern (Communist International). In 1923, when the young party entered into an alliance with Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist Party ([[Kuomintang]]), Mao was one of the first communists to join the Nationalist Party and to work within it. During the first half of 1924, he lived mostly with his wife and two infant sons in Shanghai, where he was a leading member of the Nationalists’ Executive Bureau. | |||

In the winter of 1924–25, Mao returned to his native village of Shaoshan for a rest. There, after witnessing demonstrations by peasants stirred into political consciousness by the shooting of several dozen Chinese by foreign police in Shanghai (May and June 1925), Mao suddenly became aware of the revolutionary potential inherent in the peasantry. Although born in a peasant household, he had, in the course of his student years, adopted the Chinese intellectual’s traditional view of the workers and peasants as ignorant and dirty. His conversion to Marxism had forced him to revise his estimate of the urban proletariat, but he continued to share Marx’s own contempt for the backward and amorphous peasantry. Now he turned back to the rural world of his youth as the source of China’s regeneration. Following the example of other communists working within the Nationalist Party who had already begun to organize the peasants, Mao sought to channel the spontaneous protests of the Hunanese peasants into a network of peasant associations. | |||

==== The Communists And The Nationalists ==== | |||

Pursued by the military governor of Hunan, Mao was soon forced to flee his native province once more, and he returned for another year to an urban environment—Guangzhou (Canton), the main power base of the Nationalists. However, though he lived in Guangzhou, Mao still focused his attention on the countryside. He became the acting head of the propaganda department of the Nationalist Party—in which capacity he edited its leading organ, the <em>Political Weekly</em>, and attended the Second Kuomintang Congress in January 1926—but he also served at the Peasant Movement Training Institute, set up in Guangzhou under the auspices of the Nationalists, as principal of the sixth training session. [[Chiang Kai-shek]] (Jiang Jieshi) had become the leader of the Nationalists after the death of Sun Yat-sen in March 1925, and, although Chiang still declared his allegiance to the “world revolution” and wished to avail himself of aid from the Soviet Union, he was determined to remain master in his own house. He therefore expelled most communists from responsible posts in the Nationalist Party in May 1926. Mao, however, stayed on at the institute until October of that year. Most of the young peasant activists Mao trained were shortly at work strengthening the position of the communists. | |||

In July 1926 Chiang Kai-shek set out on what became known as the Northern Expedition, aiming to unify the country under his own leadership and to overthrow the conservative government in Beijing as well as other warlords. In November Mao once more returned to Hunan; there, in January and February 1927, he investigated the peasant movement and concluded that in a very short time several hundred million peasants in China would “rise like a tornado or tempest—a force so extraordinarily swift and violent that no power, however great, will be able to suppress it.” Strictly speaking, that prediction proved to be false. Revolution in the shape of spontaneous action by hundreds of millions of peasants did not sweep across China “in a very short time,” or indeed at all. Chiang Kai-shek, who was bent on an alliance with the propertied classes in the cities and in the countryside, turned against the worker and peasant revolution, and in April he massacred the very Shanghai workers who had delivered the city to him. The strategy of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin for carrying out revolution in alliance with the Nationalists collapsed, and the CCP was virtually annihilated in the cities and decimated in the countryside. In a broader and less literal sense, however, Mao’s prophecy was justified. In October 1927 Mao led a few hundred peasants who had survived the autumn harvest uprising in Hunan to a base in the Jinggang Mountains, on the border between Jiangxi and Hunan provinces, and embarked on a new type of revolutionary warfare in the countryside in which the Red Army (military arm of the CCP), rather than the unarmed masses, would play the central role. But it was only because a large proportion of China’s hundreds of millions of peasants sympathized with and supported that effort that Mao Zedong was able in the course of the protracted [[Civil War|civil war]] to encircle the cities from the countryside and thus eventually defeat Chiang Kai-shek and gain control of the country. | |||

The | ==== The Road To Power ==== | ||

[[File:Mao-Zedong-group-followers-1944.jpg|thumb|249x249px|Mao Zedong addressing a group of his followers in 1944.|link=Special:FilePath/Mao-Zedong-group-followers-1944.jpg]] | |||

Mao Zedong’s 22 years in the wilderness can be divided into four phases. The first of those is the initial three years when Mao and Zhu De, the commander in chief of the army, successfully developed the tactics of guerrilla warfare from base areas in the countryside. Those activities, however, were regarded even by their protagonists, and still more by the Central Committee in Shanghai (and by the Comintern in Moscow), as a holding operation until the next upsurge of revolution in the urban centers. In the summer of 1930 the Red Army was ordered by the Central Committee to occupy several major cities in south-central China in the hope of sparking a revolution by the workers. When it became evident that persistence in that attempt could only lead to further costly losses, Mao disobeyed orders and abandoned the battle to return to the base in southern Jiangxi. During that year Mao’s wife was executed by the Nationalists, and he married He Zizhen, with whom he had been living since 1928. | |||

The | The second phase (the Ziangxi period) centers on the founding in November 1931 of the Jiangxi Soviet (Chinese Soviet Republic) in a portion of Jiangxi province, with Mao as chairman. Since there was little support for the revolution in the cities, the promise of ultimate victory now seemed to reside in the gradual strengthening and expansion of the base areas. The Soviet regime soon came to control a population of several million. The Red Army, grown to a strength of some 200,000, easily defeated large forces of inferior troops sent against it by Chiang Kai-shek in the first four of the so-called encirclement and annihilation campaigns. But it was unable to stand up against Chiang’s own elite units, and in October 1934 the major part of the Red Army, Mao, and his pregnant wife abandoned the base in Jiangxi and set out for the northwest of China, on what is known as the Long March. | ||

There is wide disagreement among specialists as to the extent of Mao’s real power, especially in the years 1932–34, and as to which military strategies were his or other party leaders’. The majority view is that, in the last years of the Jiangxi Soviet, Mao functioned to a considerable extent as a figurehead with little control over policy, especially in military matters. In any case, he achieved de facto leadership over the party (though not the formal title of chairman) only at the Zunyi Conference of January 1935 during the Long March. | |||

When some 8,000 troops who had survived the perils of the Long March arrived in Shaanxi province in northwestern China in the autumn of 1935, events were already moving toward the third phase in Mao’s rural odyssey, which was to be characterized by a renewed united front with the Nationalists against Japan and by the rise of Mao to unchallenged supremacy in the party. That phase is often called the Yan’an period (for the town in Shaanxi where the communists were based), although Mao did not move to Yan’an until December 1936. In August1935 the Comintern at its Seventh Congress in Moscow proclaimed the principle of an antifascist united front, and in May 1936 the Chinese communists for the first time accepted the prospect that such a united front might include Chiang Kai-shek himself, and not merely dissident elements in the Nationalist camp. The so-called Xi’an Incident of December 1936, in which Chiang was [[Kidnapping|kidnapped]] by military leaders from northeastern China who wanted to fight Japan and recover their homelands rather than participate in civil war against the communists, accelerated the evolution toward unity. By the time the Japanese began their attempt to subjugate all of China in July 1937, the terms of a new united front between the communists and the Nationalists had been virtually settled, and the formal agreement was announced in September 1937. | |||

In the course of the anti-Japanese war, the communists broke up a substantial portion of their army into small units and sent them behind the enemy lines to serve as nuclei for guerrilla forces that effectively controlled vast areas of the countryside, stretching between the cities and communication lines occupied by the invader. As a result, they not only expanded their military forces to somewhere between a half-million and a million at the time of the Japanese surrender but also established effective grassroots political control over a population that may have totaled as many as 90 million. It has been argued that the support of the rural population was won purely by appeals to their nationalist feeling in opposition to the Japanese. That certainly was fundamental, but communist agrarian policies likewise played a part in securing broad support among the peasantry. | |||

During the years 1936–40, Mao had, for the first time since the 1920s, the leisure to devote himself to reflection and writing. It was then that he first read in translation a certain number of Soviet writings on philosophy and produced his own account of dialectical materialism, of which the best-known portions are those entitled “On Practice” and “On Contradiction.” More important, Mao produced the major works that synthesized his own experience of revolutionary struggle and his vision of how the revolution should be carried forward in the context of the united front. On military matters there was first <em>Strategic Problems of China’s Revolutionary War</em>, written in December 1936 to sum up the lessons of the Jiangxi period (and also to justify the correctness of his own military line at the time), and then <em>On Protracted War</em> and other writings of 1938 on the tactics of the anti-Japanese war. As to his overall view of the events of those years, Mao adopted an extremely conciliatory attitude toward the Nationalists in his report entitled <em>On the New Stage</em> (October 1938), in which he attributed to it the leading role both in the war against Japan and in the ensuing phase of national reconstruction. By the winter of 1939–40, however, the situation had changed sufficiently so that he could adopt a much firmer line, claiming leadership for the communists. Internationally, Mao argued, the Chinese revolution was a part of the world proletarian revolution directed against imperialism (whether it be British, German, or Japanese); internally, the country should be ruled by a “joint dictatorship of several parties” belonging to the anti-Japanese united front. For the time being, Mao felt, the aims of the CCPcoincided with the aims of the Nationalists, and therefore communists should not try to rush ahead to socialism and thus disrupt the united front. But neither should they have any doubts about the ultimate need to take power into their own hands in order to move forward to socialism. During that period, in 1939, Mao divorced He Zizhen and married a well-known film actress, Lan Ping (who by that time had changed her name to [[Jiang Qing]]). | |||

The issues of Nationalist-communist rivalry for the leadership of the united front are related to the continuing struggle for supremacy within the CCP, for Mao’s two chief rivals—Wang Ming, who had just returned from a long stay in Moscow, and Zhang Guotao, who had at first refused to accept Mao’s political and military leadership—were both accused of excessive slavishness toward the Nationalists. But perhaps even more central in Mao’s ultimate emergence as the acknowledged leader of the party was the question of what he had called in October 1938 the “Sinification” of Marxism—its adaptation not only to Chinese conditions but to the mentality and cultural traditions of the Chinese people. | |||

Mao could not claim the firsthand knowledge possessed by many other leading members of the CCP of how communism worked within the Soviet Union nor the ability to read Karl Marx or [[Vladimir Lenin]] in the original, which some of them enjoyed. He could and did claim, however, to know and understand China. The differences between him and the Soviet-oriented faction in the party came to a head at the time of the so-called Rectification Campaign of 1942–43. That program aimed at giving a basic grounding in Marxist theory and Leninist principles of party organization to the many thousands of new members who had been drawn into the party in the course of the expansion since 1937. But a second and equally important aspect of the movement was the elimination of what Mao called “foreign dogmatism”—in other words, blind imitation of Soviet experience and obedience to Soviet directives. | |||

In March 1943 Mao achieved for the first time formal supremacy over the party, becoming chairman of the Secretariat and of the Political Bureau (Politburo). Shortly thereafter the Rectification Campaign took, for a time, the form of a harsh purge of elements not sufficiently loyal to Mao. The campaign was run by Kang Sheng, who was later to be one of Mao’s key supporters in the Cultural Revolution. Exaggerating considerably that dimension of events, Soviet spokesmen have bitterly denounced the Rectification Campaign as an attempt to purge the CCP of all those elements genuinely imbued with “proletarian internationalism” (i.e., devotion to Moscow). It is therefore not surprising that, as Mao’s campaign in the countryside moved into its fourth and last phase—that of civil war with the Nationalists—Stalin’s lack of enthusiasm for a Chinese communist victory should have become increasingly evident. Looking back at that period in 1962, when the Sino-Soviet conflict had come to a head, Mao declared: | |||

{{Quote|In 1945, Stalin wanted to prevent China from making revolution, saying that we should not have a civil war and should cooperate with Chiang Kai-shek, otherwise the Chinese nation would perish. But we did not do what he said. The revolution was victorious. After the victory of the revolution he [Stalin] next suspected China of being a Yugoslavia, and that I would become a second Tito.}} | |||

That account of Stalin’s attitude is substantiated by a whole series of public gestures at the time, culminating in the fact that, when the People’s Liberation Army (successor to the Red Army) took the Nationalist capital of Nanjing in April 1949, the Soviet ambassador was the only foreign diplomat to accompany the retreating Nationalist government to Guangzhou. Stalin’s motives were obviously those described by Mao in the above passage; he did not believe in the capacity of the Chinese communists to achieve a clear-cut victory, and he thought they would be a nuisance if they did. | |||

==== Formation Of The People’s Republic Of China ==== | |||

Nevertheless, when the communists did take power in China, both Mao and Stalin had to make the best of the situation. In December 1949 Mao, now chairman of the People’s Republic of China—which he had proclaimed on October 1—traveled to Moscow, where, after two months of arduous negotiations, he succeeded in persuading Stalin to sign a treaty of mutual assistance accompanied by limited economic aid. Before the Chinese had time to profit from the resources made available for economic development, however, they found themselves dragged into the [[Korean War]] in support of [[Kim Il-sung]]'s Moscow-oriented regime in North Korea. Only after that baptism of fire did Stalin, according to Mao, begin to have confidence in him and believe he was not first and foremost a Chinese nationalist. | |||

Despite those tensions with Moscow, the policies of the People’s Republic of China in its early years were in very many respects based, as Mao later said, on “copying from the Soviets.” While Mao and his comrades had experience in guerrilla warfare, in mobilization of the peasants in the countryside, and in political administration at the grass roots, they had no firsthand knowledge of running a state or of large-scale economic development. In such circumstances the Soviet Union provided the only available model. A five-year plan was therefore drawn up under Soviet guidance; it was put into effect in 1953 and included Soviet technical assistance and a number of complete industrial plants. Yet, within two years, Mao had taken steps that were to lead to the breakdown of the political and ideological alliance with Moscow. | |||

== | ==== The Emergence Of Mao’s Road To Socialism ==== | ||

Mao | In the spring of 1949, Mao proclaimed that, while in the past the Chinese revolution had followed the unorthodox path of “encircling the cities from the countryside,” it would in the future take the orthodox road of the cities leading and guiding the countryside. In harmony with that view, he had agreed in 1950 with Liu Shaoqi that collectivization would be possible only when China’s heavy industry had provided the necessary equipment for mechanization. In a report of July 1955, he reversed that position, arguing that in China the social transformation could run ahead of the technical transformation. Deeply impressed by the achievements of certain cooperatives that claimed to have radically improved their material conditions without any outside assistance, he came to believe in the limitless capacity of the Chinese people, especially of the rural masses, to transform at will both nature and their own social relations when mobilized for revolutionary goals. Those in the leadership who did not share that vision he denounced as “old women with bound feet.” He made those criticisms before an ad hoc gathering of provincial and local party secretaries, thus creating a groundswell of enthusiasm for rapid collectivization such that all those in the leadership who had expressed doubts about Mao’s ideas were soon presented with a fait accompli. The tendency thus manifested to pursue his own ends outside the collective decision-making processes of the party was to continue and to be accentuated. | ||

Even before Stalin’s successor, [[Nikita Khrushchev]], had given his secret speech (February 1956) denouncing his predecessor’s crimes, Mao Zedong and his colleagues had been discussing measures for improving the morale of the intellectuals in order to secure their willing participation in building a new China. At the end of April, Mao proclaimed the policy of “letting a hundred flowers bloom”—that is, the freedom to express many diverse ideas—designed to prevent the development in China of a repressive political climate analogous to that in the Soviet Union under Stalin. In the face of the disorders called forth by de-Stalinization in Poland and Hungary, Mao did not retreat but rather pressed boldly forward with that policy, against the advice of many of his senior colleagues, in the belief that the contradictions that still existed in Chinese society were mainly nonantagonistic. When the resulting “great blooming and contending” got out of hand and called into question the axiom of party rule, Mao savagely turned against the educated elite, which he felt had betrayed his confidence. Henceforth he would rely primarily on the creativity of the rank and file as the agent of modernization. As for the specialists, if they were not yet sufficiently “red,” he would remold them by sending them to work in the countryside. | |||

He was | It was against that background that Mao, during the winter of 1957–58, worked out the policies that were to characterize the Great Leap Forward, formally launched in May 1958. While his economic strategy was by no means so one-sided and simplistic as was commonly believed in the 1960s and ’70s and although he still proclaimed industrialization and a “technical revolution” as his goals, Mao displayed continuing anxiety regarding the corrupting influence of the fruits of technical progress and an acute nostalgia for the perceived purity and egalitarianism that had marked the moral and political world of the Jinggang Mountains and Yan’an eras. | ||

Thus it was logical that he should endorse and promote the establishment of “people’s communes” as part of the Great Leap strategy. As a result, the peasants, who had been organized into cooperatives in 1955–56 and then into fully socialist collectives in 1956–57, found their world turned upside down once again in 1958. Neither the resources nor the administrative experience necessary to operate such enormous new social units of several thousand households were in fact available, and, not surprisingly, the consequences of those changes were chaosand economic disaster. | |||

By the winter of 1958–59, Mao himself had come to recognize that some adjustments were necessary, including decentralization of ownership to the constituent elements of the communes and a scaling down of the unrealistically high production targets in both industry and agriculture. He insisted, however, that in broad outline his new Chinese road to socialism, including the concept of the communes and the belief that China, though “poor and blank,” could leap ahead of other countries, was basically sound. At the Lushan meeting of the Central Committee in July–August 1959, Peng Dehuai, the minister of defense, denounced the excesses of the Great Leap and the economic losses they had caused. He was immediately removed from all party and state posts and placed in detention until his death during the Cultural Revolution. From that time, Mao regarded any criticism of his policies as nothing less than a crime of lèse-majesté, meriting exemplary punishment. | |||

==== Retreat And Counterattack ==== | |||

Though few spoke up at Lushan in support of Peng, a considerable number of the top leaders sympathized with him in private. Almost immediately, in 1960, Mao began building an alternative power base in the People’s Liberation Army, which the new defense minister, [[Lin Biao]], had set out to turn into a “great school of Mao Zedong Thought.” At about the same time, Mao began to denounce the emergence, not only in the Soviet Union but also in China itself, of “new bourgeois elements” among the privileged strata of the state and party bureaucracy and the technical and artistic elite. Under those conditions, he concluded, a “protracted, complex, and sometimes even violent class struggle” would continue during the whole socialist stage. | |||

The open split with the Soviet Union, which had become public and irreparable by 1963—though it can be traced to Mao’s resentment at Khrushchev’s failure to consult him before launching de-Stalinization—resulted, above all, from the Soviet reaction to the Great Leap policies. Khrushchev regarded Mao’s claims for the communes as ideologically presumptuous, and he heaped ridicule on them; he underlined his displeasure by withdrawing Soviet technical assistance in 1960, leaving many large industrial plants unfinished. Khrushchev also tried to put pressure on China in its dealings with Taiwan and India and in other foreign policy issues. Mao forgot neither the affront to his and China’s dignity nor the economic damage. | |||

As for class struggle in China itself, Mao’s fear that revisionism might appear there was heightened by the policies pursued in the early 1960s to deal with the economic consequences of the Great Leap Forward. The disorganization and waste created by the Great Leap, compounded by natural disasters and by the termination of Soviet economic aid, led to widespread famine in which, according to much later official Chinese accounts, millions of people died. The response to that situation by Liu Shaoqi (who had succeeded Mao as chairman of the People’s Republic in 1959), [[Deng Xiaoping]], and the economic planners was to make use of material incentives and to strengthen the role of individual households in agricultural production. At first Mao agreed reluctantly that such steps were necessary, but during the first half of 1962 he came increasingly to perceive the methods used to promote recovery as implying the repudiation of the whole thrust of the Great Leap strategy. It was as a direct response to that challenge that at the 10th Plenary Session of the Central Committee in September 1962 he issued the call, “Never forget the class struggle!” | |||

During the next three years Mao waged such a struggle, primarily through the Socialist Education Movement in the countryside, and it was over the guidelines for that campaign that the major political battles were fought within the Chinese leadership. At the end of 1964, when Liu Shaoqi refused to accept Mao’s demand to direct the main thrust of class struggle against “capitalist roaders” in the party, Mao decided that “Liu had to go.” | |||

==== The Cultural Revolution ==== | |||

The movement that became known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution represented an attempt by Mao to go beyond the party rectification campaigns—of which there had been many since 1942—and to devise a new and more radical method for dealing with what he saw as the bureaucratic degeneration of the party. It also represented, beyond any doubt or question, however, a deliberate effort to eliminate those in the leadership who, over the years, had dared to cross him. The victims, from throughout the party hierarchy, suffered more than mere political disgrace. All were publicly humiliated and detained for varying periods, sometimes under very harsh conditions; many were beaten and tortured, and not a few were killed or driven to suicide. Among the casualties was Liu, who died because he was denied proper medical attention. | |||

The justification for those sacrifices was defined in a key slogan of the time: “Fight selfishness, criticize revisionism.” When the young Chinese known as the [[Red Guards]], who constituted the first shock troops of Mao’s enterprise, burst onto the scene in the summer of 1966 with their battle cry “To rebel is justified!” it seemed for a time that not only the power of the party cadres but also authority in all its forms was being questioned. It soon became evident that Mao, who in 1956 had justified decentralization as a means to building a “strong socialist state,” still believed in the need for state power. When the Shanghai leftists Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan—who were later to make up half the Gang of Four—came to see him in February 1967, immediately after setting up the Shanghai Commune, Mao asserted that the demand for the abolition of “heads” (leaders), which had been heard in their city, was “extreme anarchism” and “most reactionary”; in fact, he stated, there would “always be heads.” Communes, he added, were “too weak when it came to suppressing counterrevolution” and in any case required party leadership. He therefore ordered them to dissolve theirs and to replace it with a “revolutionary committee.” | |||

Those committees, based on an alliance of former party cadres, young activists, and representatives of the People’s Liberation Army, were to remain in place until two years after Mao’s death. At first they were largely controlled by the army. The Ninth Congress of 1969 initiated the process of rebuilding the party; and the death of Lin Biao in 1971 diminished, though it by no means eliminated, the army’s role. Thereafter it seemed briefly, in 1971–72, that a compromise, of which [[Zhou Enlai]] was the architect, might produce some kind of synthesis between the values of the Cultural Revolution and the pre-1966 political and economic order. | |||

He was one of the main supporters of [[Pol Pot]] and his [[Khmer Rouge]] during the Cambodian Civil War. Upon the Khmer Rouge taking power in 1975, Pol Pot largely based his "Year Zero" policies on Mao's Cultural Revolution, which would ultimately result in the [[Cambodian Genocide]]. Mao would serve as the Khmer Rouge's primary supporter during their years in power, after Vietnam distanced themselves from the regime. He also was a strong ally of [[Ho Chi Minh]] (and later [[Le Duan]]) during the [[Vietnam War]]. | |||

Even before Zhou’s death in January 1976, however, that compromise had been overturned. All recognition by Mao of the importance of professional skills was swallowed up in an orgy of political rhetoric, and all things foreign were regarded as counterrevolutionary. Mao’s last decade, which had opened with manifestos in favour of the Paris Commune model of mass democracy, closed with paeans of praise to that most implacable of centralizing despots, Shihuangdi, the first emperor of the ancient Qin dynasty. | |||

==== Death ==== | |||

Mao's last public appearance—and the last known photograph of him alive—was on May 27, 1976, when he met the visiting Pakistani Prime Minister [[Zulfikar Ali Bhutto]] during the latter's one-day visit to Beijing. At around 5:00 pm on 2 September 1976, Mao suffered a heart attack, far more severe than his previous two and affecting a much larger area of his heart. Three days later, on 5 September another heart attack randered him an invalid. On the afternoon of 7 September, Mao's condition completely deteriorated. Mao's organs failed quickly and he fell into a coma shortly before noon where he was put on life support machines. | |||

Mao Zedong died nearly four days later just after midnight, at 00:10, on September 9, 1976, at age 82. The Communist Party of China delayed the announcement of his death until 16:00 later that day, when a radio message broadcast across the nation announced the news of Mao's passing while appealing for party unity. | |||

Mao's embalmed, CPC-flag-draped body lay in state at the Great Hall of the People for one week.<sup>[16]</sup> During this period, one million people (none of them foreign diplomats, and many crying openly or displaying some kind of sadness) filed past Mao to pay their final respects. Chairman Mao's official portrait was hung on the wall, with a banner reading: "Carry on the cause left by Chairman Mao and carry on the cause of proletarian revolution to the end", until September 17. On September 17, Chairman Mao's body was taken in a minibus from the Great Hall of the people to Maojiawan to the 305 Hospital that Liu Zhisui directed, and Mao's internal organs were preserved in formaldehyde. | |||

On September 18, guns, sirens, whistles and horns across China were simultaneously blown and a mandatory three-minute silence was observed. Tiananmen Square was packed with millions of people and a military band played "The Internationale". [[Hua Guofeng]], who would go on to succeed Mao as Chairman, concluded the service with a 20-minute-long eulogy atop Tiananmen Gate. Despite Mao's request to be cremated, his body was later permanently put on display in the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong, in order for the Chinese nation to pay its respects. | |||

== Legacy == | |||

{{Quote|But if you go carrying pictures of Chairman Mao<br>You ain't gonna make it with anyone anyhow.<br>|The Beatles, "Revolution"}}[[File:Mao Zedong portrait.jpg|thumb|263x263px|Portrait of Mao Zedong.]] | |||

While the Cultural Revolution was an entirely logical culmination of Mao's last two decades, it was by no means the only possible outcome of his approach to revolution, nor need a judgment of his work as a whole be based primarily on that last phase. | |||

Few would deny Mao Zedong the major share of credit for devising the pattern of struggle based on guerrilla warfare in the countryside that ultimately led to victory in the civil war and thereby to the overthrow of the Nationalists, the distribution of land to the peasants, and the restoration of China's independence and sovereignty. Those achievements must be given a weight commensurate with the degree of injustice prevailing in Chinese society before the revolution and with the humiliation felt by the Chinese people as a result of the dismemberment of their country by the foreign powers. "We have stood up," Mao said in September 1949. Those words will not be forgotten. | |||

Mao's record after 1949 is more ambiguous. The official Chinese view, defined in June 1981, is that his leadership was basically correct until the summer of 1957, but from then on it was mixed at best and frequently wrong. It cannot be disputed that Mao’s two major innovations of his later years, the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution, were ill-conceived and led to disastrous consequences. His goals of combating bureaucracy, encouraging popular participation, and stressing China’s self-reliance were generally laudable—and the industrialization that began during Mao’s reign did indeed lay a foundation for China’s remarkable economic development since the late 20th century—but the methods he used to pursue them were often violent and self-defeating. | |||

There is no single accepted measure of Mao and his long career. How does one weigh, for example, the good fortune of peasants acquiring land against millions of executions and deaths? How does one balance the real economic achievements after 1949 against the starvation that came in the wake of the Great Leap Forward or the bloody shambles of the Cultural Revolution? It is, perhaps, possible to accept the official verdict that, despite the "errors of his later years," Mao's merits outweighed his faults, while underscoring the fact that the account is very finely balanced. | |||

==Trivia== | |||

*Mao personally didn't like purging his officials despite seeing it as necessary. | |||

*Mao was reportedly a great swimmer and it has been said that he managed to swim across a flowing river in a very short amount of time. | |||

*Mao Zedong, despite being a repressive controversial dictator that caused millions of deaths, was against imperialism and fought as a general in the Second Sino-Japanese War against [[Imperial Japan]], a conflict that saw him briefly join forces with future Taiwanese dictator Chiang Kai-Shek and the [[Kuomintang]]. Furthermore, Mao was so disgusted by the horrific [[Rape of Nanking]] committed by Japanese forces during the war that he refused to speak of the horrendous atrocity for the rest of his life. | |||

**However he rather thanked Japan for invading China, He ironically said these words: ''" Don't say that, on the contrary, Japanese helped us (Communist) in a big way. "'' Meaning he refused to accept Japan's apology and rather thanked the Japanese invasion of Mainland China as well as supporting the denials of Nanking Massacre until his death in 1976 the rise of Anti-Japanese sentiment rose. | |||

**According to Watchmojo's [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9yPMWpjN9k&t=173s 10 Most EVIL Men in History video], Mao Zedong is the sixth most evil man in the history of mankind. | |||

==Videos== | |||

<YouTube width=320 height=180>https://youtu.be/PJIIZm_JO_4</YouTube> | |||

<YouTube width=320 height=180>https://youtu.be/fsME7AXcf6E</YouTube> | |||

<YouTube width=320 height=180>https://youtu.be/g_2FZ-V_4zs</YouTube> | |||

<YouTube width=320 height=180>https://youtu.be/uWKNVZqC0yo</YouTube> | |||

<YouTube width=320 height=180>https://youtu.be/oSmHz1S9K2Q</YouTube> | |||

<YouTube width=320 height=180>https://youtu.be/dW_ekZRGalk</YouTube> | |||

[[Category:List]] | [[Category:List]] | ||

[[Category:Leader]] | [[Category:Leader]] | ||

[[Category:Business Leaders]] | [[Category:Business Leaders]] | ||

[[Category:Karma Houdini]] | |||

[[Category:Deceased]] | |||

[[Category:Evil vs. Evil]] | |||

[[Category:Elderly]] | |||

[[Category:Master Manipulator]] | |||

[[Category:Failure-Intolerant]] | |||

[[Category:Honorable Villains]] | |||

[[Category:Murderer]] | |||

[[Category:Tragic]] | |||

[[Category:Psychopath]] | |||

[[Category:God Wannabe]] | |||

[[Category:Emotionless Villains]] | |||

[[Category:Mentally Ill]] | |||

[[Category:Starvers]] | |||

[[Category:Charismatic]] | |||

[[Category:Jingoists]] | |||

[[Category:Lawful Evil]] | |||

[[Category:Government support]] | |||

[[Category:Perverts]] | |||

[[Category:Pimps]] | |||

[[Category:Posthumous]] | |||

[[Category:Weapon Dealer]] | |||

[[Category:Ableist]] | |||

[[Category:Villains of World War 2]] | |||

[[Category:Wealthy]] | |||

[[Category:Dark Priest]] | |||

[[Category:Supremacists]] | |||

[[Category:Irony]] | |||

[[Category:Mutilators]] | |||

[[Category:Polluters]] | |||

[[Category:Brutes]] | |||

[[Category:Dark Messiah]] | |||

[[Category:Eco Destroyer]] | [[Category:Eco Destroyer]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Warlords]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Muses]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Delusional]] | ||

[[Category:Genocidal]] | |||

[[Category:Propagandist]] | |||

[[Category:Mastermind]] | |||

[[Category:Brainwasher]] | [[Category:Brainwasher]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Elitist]] | ||

[[Category:Traitor]] | |||

[[Category:Xenophobes]] | |||

[[Category:Social Darwinist]] | |||

[[Category:Incriminator]] | |||

[[Category:Control Freaks]] | |||

[[Category:Extremists]] | |||

[[Category:Political]] | [[Category:Political]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Animal Cruelty]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Iconoclasts]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Barbarians]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Thief]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Cold war villains]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Male]] | ||

[[Category:Wrathful]] | |||

[[Category:Usurper]] | |||

[[Category:Obsessed]] | |||

[[Category:Egotist]] | |||

[[Category:Arrogant]] | |||

[[Category:Military]] | |||

[[Category:Fanatics]] | |||

[[Category:Extravagant]] | |||

[[Category:Anti-Catholic]] | |||

[[Category:Anti-Religious]] | |||

[[Category:Anti-Christian]] | |||

[[Category:Adulterers]] | |||

[[Category:Oppressors]] | |||

[[Category:Destroyer]] | |||

[[Category:War Criminal]] | |||

[[Category:Mongers]] | |||

[[Category:Artistic]] | |||

[[Category:Vengeful]] | |||

[[Category:Psychological Abusers]] | |||

[[Category:Destroyer of Innocence]] | |||

[[Category:Anti-Semitic]] | |||

[[Category:Conspirators]] | |||

[[Category:Power Hungry]] | [[Category:Power Hungry]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Tyrants]] | ||

[[Category:Modern Villains]] | [[Category:Modern Villains]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Thugs]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Liars]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Arsonist]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Aristocrat]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Con Artists]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Extortionists]] | ||

[[Category:Abusers]] | |||

[[Category:Fallen Heroes]] | |||

[[Category:Smuggler]] | |||

[[Category:Misanthropes]] | [[Category:Misanthropes]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Misogynists]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Misopedists]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Paranoid]] | ||

[[Category:Villains | [[Category:Hegemony]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Kidnapper]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Totalitarians]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Communist]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Anarchist]] | ||

[[Category:Islamophobes]] | |||

[[Category:Wolves in sheep's clothing]] | |||

[[Category:Drug Dealers]] | |||

[[Category:Homicidal]] | |||

[[Category:Mass Murderers]] | |||

[[Category:China]] | |||

[[Category:Bully]] | |||

[[Category:Provoker]] | |||

[[Category:Slaver]] | |||

[[Category:Torturer]] | |||

[[Category:Anti-LGBT]] | |||

[[Category:China]] | |||

[[Category:Successful]] | |||

[[Category:Corrupting Influence]] | |||

[[Category:Corrupt Officials]] | |||

[[Category:Asian Villains]] | |||

[[Category:Saboteurs]] | |||

[[Category:Greedy]] | |||

[[Category:Affably Evil]] | |||

[[Category:Early Modern Villains]] | |||

Latest revision as of 06:07, 3 January 2025

|

| “ | Politics is war without bloodshed, while war is politics with bloodshed. | „ |

| ~ Mao Zedong |

Mao Zedong (December 26th, 1893 - September 9th, 1976), commonly known as Chairman Mao, was the Communist Leader of the People's Republic of China from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976 and led the "Great Leap Forward" movement to break all traditions of Ancient China. His Cultural Revolution all but destroyed China's heritage.

A major player in the Cold War, Mao is considered to be a pioneer of communism alongside Joseph Stalin, developing his own brand of communism known as Maoism (also known as Mao Zedong Thought). He also pioneered the People's War strategy commonly used by many Communists in armed struggle.

Although many of Mao's campaigns, most notably The Great Leap Forward lead to the death of millions, many historians have pointed out that many of the deaths under Mao's regime were unintentional unlike many of the deaths under Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union. He is widely considered one of the most polarizing and controversial figures in recent history, many regard him as a capable and necessary leader who improved health care, women's rights and industrialized China and see many of his campaigns as taking significant risks, while in contrast his critics have drawn comparisons between him and dictators such as Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler due to his radically destructive and neglectful polices against his own people. Some estimates say that between 30 million-80 million people in total died under his regime and for this reason he is considered by some historians to be the most brutal dictator in history.

Biography edit

Early life edit

Mao was born in the village of Shaoshan in Hunan province, the son of a former peasant who had become affluent as a farmer and grain dealer. He grew up in an environment in which education was valued only as training for keeping records and accounts. From the age of eight he attended his native village’s primary school, where he acquired a basic knowledge of the Wujing (Confucian Classics). At 13 he was forced to begin working full-time on his family’s farm. Rebelling against paternal authority (which included an arranged marriage that was forced on him and that he never acknowledged or consummated), Mao left his family to study at a higher primary school in a neighbouring county and then at a secondary school in the provincial capital, Changsha. There he came in contact with new ideas from the West, as formulated by such political and cultural reformers as Liang Qichao and the Nationalist revolutionary Sun Yat-sen. Scarcely had he begun studying revolutionary ideas when a real revolution took place before his very eyes. On October 10, 1911, fighting against the Qing dynastybroke out in Wuchang, and within two weeks the revolt had spread to Changsha.

Enlisting in a unit of the revolutionary army in Hunan, Mao spent six months as a soldier. While he probably had not yet clearly grasped the idea that, as he later put it, “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun,” his first brief military experience at least confirmed his boyhood admiration of military leaders and exploits. In primary school days, his heroes had included not only the great warrior-emperors of the Chinese past but Napoleon I and George Washington as well.

The spring of 1912 marked the birth of the new Chinese republic and the end of Mao’s military service. For a year he drifted from one thing to another, trying, in turn, a police school, a law school, and a business school; he studied history in a secondary school and then spent some months reading many of the classic works of the Western liberal tradition in the provincial library. That period of groping, rather than indicating any lack of decision in Mao’s character, was a reflection of China’s situation at the time. The abolition of the official civil service examination system in 1905 and the piecemeal introduction of Western learning in so-called modern schools had left young people in a state of uncertainty as to what type of training, Chinese or Western, could best prepare them for a career or for service to their country.

Mao eventually graduated from the First Provincial Normal School in Changsha in 1918. While officially an institution of secondary level rather than of higher education, the normal school offered a high standard of instruction in Chinese history, literature, and philosophy as well as in Western ideas. While at the school, Mao also acquired his first experience in political activity by helping to establish several student organizations. The most important of those was the New People’s Study Society, founded in the winter of 1917–18, many of whose members were later to join the Communist Party.

From the normal school in Changsha, Mao went to Peking University in Beijing, China’s leading intellectual center. The half year he spent there working as a librarian’s assistant was of disproportionate importance in shaping his future career, for it was then that he came under the influence of the two men who were to be the principal figures in the foundation of the CCP: Li Dazhao and Chen Duxiu. Moreover, he found himself at Peking University precisely during the months leading up to the May Fourth Movement of 1919, which was to a considerable extent the fountainhead of all of the changes that were to take place in China in the ensuing half century.

In a limited sense, May Fourth Movement is the name given to the student demonstrations protesting against the decision at the Paris Peace Conference to hand over former German concessions in Shandong province to Japan instead of returning them to China. But the term also evokes a period of rapid political and cultural change, beginning in 1915, that resulted in the Chinese radicals’ abandonment of Western liberalism for Marxism and Leninism as the answer to China’s problems and the subsequent founding of the Chinese Communist Party in 1921. The shift from the difficult and esoteric classical written language to a far more-accessible vehicle of literary expression patterned on colloquial speech also took place during that period. At the same time, a new and very young generation moved to the centre of the political stage. To be sure, the demonstration on May 4, 1919, was launched by Chen Duxiu, but the students soon realized that they themselves were the main actors.

From then onward his generation never ceased to regard itself as responsible for the country’s fate, and, indeed, its members remained in power, both in Beijing and in Taipei (Taiwan), until the 1970s.

During the summer of 1919 Mao Zedong helped to establish in Changsha a variety of organizations that brought the students together with the merchants and the workers—but not yet with the peasants—in demonstrations aimed at forcing the government to oppose Japan. His writings at the time are filled with references to the “army of the red flag” throughout the world and to the victory of the Russian Revolution of 1917, but it was not until January 1921 that he was finally committed to Marxism as the philosophical basis of the revolution in China.

Role in wars and political parties edit

Mao And The Chinese Communist Party edit

In September 1920 Mao became principal of the Lin Changsha primary school, and in October he organized a branch of the Socialist Youth League there. That winter he married Yang Kaihui, the daughter of his former ethics teacher. In July 1921 he attended the First Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, together with representatives from the other communist groups in China and two delegates from the Moscow-based Comintern (Communist International). In 1923, when the young party entered into an alliance with Sun Yat-sen’s Nationalist Party (Kuomintang), Mao was one of the first communists to join the Nationalist Party and to work within it. During the first half of 1924, he lived mostly with his wife and two infant sons in Shanghai, where he was a leading member of the Nationalists’ Executive Bureau.

In the winter of 1924–25, Mao returned to his native village of Shaoshan for a rest. There, after witnessing demonstrations by peasants stirred into political consciousness by the shooting of several dozen Chinese by foreign police in Shanghai (May and June 1925), Mao suddenly became aware of the revolutionary potential inherent in the peasantry. Although born in a peasant household, he had, in the course of his student years, adopted the Chinese intellectual’s traditional view of the workers and peasants as ignorant and dirty. His conversion to Marxism had forced him to revise his estimate of the urban proletariat, but he continued to share Marx’s own contempt for the backward and amorphous peasantry. Now he turned back to the rural world of his youth as the source of China’s regeneration. Following the example of other communists working within the Nationalist Party who had already begun to organize the peasants, Mao sought to channel the spontaneous protests of the Hunanese peasants into a network of peasant associations.

The Communists And The Nationalists edit

Pursued by the military governor of Hunan, Mao was soon forced to flee his native province once more, and he returned for another year to an urban environment—Guangzhou (Canton), the main power base of the Nationalists. However, though he lived in Guangzhou, Mao still focused his attention on the countryside. He became the acting head of the propaganda department of the Nationalist Party—in which capacity he edited its leading organ, the Political Weekly, and attended the Second Kuomintang Congress in January 1926—but he also served at the Peasant Movement Training Institute, set up in Guangzhou under the auspices of the Nationalists, as principal of the sixth training session. Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi) had become the leader of the Nationalists after the death of Sun Yat-sen in March 1925, and, although Chiang still declared his allegiance to the “world revolution” and wished to avail himself of aid from the Soviet Union, he was determined to remain master in his own house. He therefore expelled most communists from responsible posts in the Nationalist Party in May 1926. Mao, however, stayed on at the institute until October of that year. Most of the young peasant activists Mao trained were shortly at work strengthening the position of the communists.

In July 1926 Chiang Kai-shek set out on what became known as the Northern Expedition, aiming to unify the country under his own leadership and to overthrow the conservative government in Beijing as well as other warlords. In November Mao once more returned to Hunan; there, in January and February 1927, he investigated the peasant movement and concluded that in a very short time several hundred million peasants in China would “rise like a tornado or tempest—a force so extraordinarily swift and violent that no power, however great, will be able to suppress it.” Strictly speaking, that prediction proved to be false. Revolution in the shape of spontaneous action by hundreds of millions of peasants did not sweep across China “in a very short time,” or indeed at all. Chiang Kai-shek, who was bent on an alliance with the propertied classes in the cities and in the countryside, turned against the worker and peasant revolution, and in April he massacred the very Shanghai workers who had delivered the city to him. The strategy of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin for carrying out revolution in alliance with the Nationalists collapsed, and the CCP was virtually annihilated in the cities and decimated in the countryside. In a broader and less literal sense, however, Mao’s prophecy was justified. In October 1927 Mao led a few hundred peasants who had survived the autumn harvest uprising in Hunan to a base in the Jinggang Mountains, on the border between Jiangxi and Hunan provinces, and embarked on a new type of revolutionary warfare in the countryside in which the Red Army (military arm of the CCP), rather than the unarmed masses, would play the central role. But it was only because a large proportion of China’s hundreds of millions of peasants sympathized with and supported that effort that Mao Zedong was able in the course of the protracted civil war to encircle the cities from the countryside and thus eventually defeat Chiang Kai-shek and gain control of the country.

The Road To Power edit

Mao Zedong’s 22 years in the wilderness can be divided into four phases. The first of those is the initial three years when Mao and Zhu De, the commander in chief of the army, successfully developed the tactics of guerrilla warfare from base areas in the countryside. Those activities, however, were regarded even by their protagonists, and still more by the Central Committee in Shanghai (and by the Comintern in Moscow), as a holding operation until the next upsurge of revolution in the urban centers. In the summer of 1930 the Red Army was ordered by the Central Committee to occupy several major cities in south-central China in the hope of sparking a revolution by the workers. When it became evident that persistence in that attempt could only lead to further costly losses, Mao disobeyed orders and abandoned the battle to return to the base in southern Jiangxi. During that year Mao’s wife was executed by the Nationalists, and he married He Zizhen, with whom he had been living since 1928.

The second phase (the Ziangxi period) centers on the founding in November 1931 of the Jiangxi Soviet (Chinese Soviet Republic) in a portion of Jiangxi province, with Mao as chairman. Since there was little support for the revolution in the cities, the promise of ultimate victory now seemed to reside in the gradual strengthening and expansion of the base areas. The Soviet regime soon came to control a population of several million. The Red Army, grown to a strength of some 200,000, easily defeated large forces of inferior troops sent against it by Chiang Kai-shek in the first four of the so-called encirclement and annihilation campaigns. But it was unable to stand up against Chiang’s own elite units, and in October 1934 the major part of the Red Army, Mao, and his pregnant wife abandoned the base in Jiangxi and set out for the northwest of China, on what is known as the Long March.

There is wide disagreement among specialists as to the extent of Mao’s real power, especially in the years 1932–34, and as to which military strategies were his or other party leaders’. The majority view is that, in the last years of the Jiangxi Soviet, Mao functioned to a considerable extent as a figurehead with little control over policy, especially in military matters. In any case, he achieved de facto leadership over the party (though not the formal title of chairman) only at the Zunyi Conference of January 1935 during the Long March.

When some 8,000 troops who had survived the perils of the Long March arrived in Shaanxi province in northwestern China in the autumn of 1935, events were already moving toward the third phase in Mao’s rural odyssey, which was to be characterized by a renewed united front with the Nationalists against Japan and by the rise of Mao to unchallenged supremacy in the party. That phase is often called the Yan’an period (for the town in Shaanxi where the communists were based), although Mao did not move to Yan’an until December 1936. In August1935 the Comintern at its Seventh Congress in Moscow proclaimed the principle of an antifascist united front, and in May 1936 the Chinese communists for the first time accepted the prospect that such a united front might include Chiang Kai-shek himself, and not merely dissident elements in the Nationalist camp. The so-called Xi’an Incident of December 1936, in which Chiang was kidnapped by military leaders from northeastern China who wanted to fight Japan and recover their homelands rather than participate in civil war against the communists, accelerated the evolution toward unity. By the time the Japanese began their attempt to subjugate all of China in July 1937, the terms of a new united front between the communists and the Nationalists had been virtually settled, and the formal agreement was announced in September 1937.

In the course of the anti-Japanese war, the communists broke up a substantial portion of their army into small units and sent them behind the enemy lines to serve as nuclei for guerrilla forces that effectively controlled vast areas of the countryside, stretching between the cities and communication lines occupied by the invader. As a result, they not only expanded their military forces to somewhere between a half-million and a million at the time of the Japanese surrender but also established effective grassroots political control over a population that may have totaled as many as 90 million. It has been argued that the support of the rural population was won purely by appeals to their nationalist feeling in opposition to the Japanese. That certainly was fundamental, but communist agrarian policies likewise played a part in securing broad support among the peasantry.

During the years 1936–40, Mao had, for the first time since the 1920s, the leisure to devote himself to reflection and writing. It was then that he first read in translation a certain number of Soviet writings on philosophy and produced his own account of dialectical materialism, of which the best-known portions are those entitled “On Practice” and “On Contradiction.” More important, Mao produced the major works that synthesized his own experience of revolutionary struggle and his vision of how the revolution should be carried forward in the context of the united front. On military matters there was first Strategic Problems of China’s Revolutionary War, written in December 1936 to sum up the lessons of the Jiangxi period (and also to justify the correctness of his own military line at the time), and then On Protracted War and other writings of 1938 on the tactics of the anti-Japanese war. As to his overall view of the events of those years, Mao adopted an extremely conciliatory attitude toward the Nationalists in his report entitled On the New Stage (October 1938), in which he attributed to it the leading role both in the war against Japan and in the ensuing phase of national reconstruction. By the winter of 1939–40, however, the situation had changed sufficiently so that he could adopt a much firmer line, claiming leadership for the communists. Internationally, Mao argued, the Chinese revolution was a part of the world proletarian revolution directed against imperialism (whether it be British, German, or Japanese); internally, the country should be ruled by a “joint dictatorship of several parties” belonging to the anti-Japanese united front. For the time being, Mao felt, the aims of the CCPcoincided with the aims of the Nationalists, and therefore communists should not try to rush ahead to socialism and thus disrupt the united front. But neither should they have any doubts about the ultimate need to take power into their own hands in order to move forward to socialism. During that period, in 1939, Mao divorced He Zizhen and married a well-known film actress, Lan Ping (who by that time had changed her name to Jiang Qing).

The issues of Nationalist-communist rivalry for the leadership of the united front are related to the continuing struggle for supremacy within the CCP, for Mao’s two chief rivals—Wang Ming, who had just returned from a long stay in Moscow, and Zhang Guotao, who had at first refused to accept Mao’s political and military leadership—were both accused of excessive slavishness toward the Nationalists. But perhaps even more central in Mao’s ultimate emergence as the acknowledged leader of the party was the question of what he had called in October 1938 the “Sinification” of Marxism—its adaptation not only to Chinese conditions but to the mentality and cultural traditions of the Chinese people.

Mao could not claim the firsthand knowledge possessed by many other leading members of the CCP of how communism worked within the Soviet Union nor the ability to read Karl Marx or Vladimir Lenin in the original, which some of them enjoyed. He could and did claim, however, to know and understand China. The differences between him and the Soviet-oriented faction in the party came to a head at the time of the so-called Rectification Campaign of 1942–43. That program aimed at giving a basic grounding in Marxist theory and Leninist principles of party organization to the many thousands of new members who had been drawn into the party in the course of the expansion since 1937. But a second and equally important aspect of the movement was the elimination of what Mao called “foreign dogmatism”—in other words, blind imitation of Soviet experience and obedience to Soviet directives.

In March 1943 Mao achieved for the first time formal supremacy over the party, becoming chairman of the Secretariat and of the Political Bureau (Politburo). Shortly thereafter the Rectification Campaign took, for a time, the form of a harsh purge of elements not sufficiently loyal to Mao. The campaign was run by Kang Sheng, who was later to be one of Mao’s key supporters in the Cultural Revolution. Exaggerating considerably that dimension of events, Soviet spokesmen have bitterly denounced the Rectification Campaign as an attempt to purge the CCP of all those elements genuinely imbued with “proletarian internationalism” (i.e., devotion to Moscow). It is therefore not surprising that, as Mao’s campaign in the countryside moved into its fourth and last phase—that of civil war with the Nationalists—Stalin’s lack of enthusiasm for a Chinese communist victory should have become increasingly evident. Looking back at that period in 1962, when the Sino-Soviet conflict had come to a head, Mao declared:

| “ | In 1945, Stalin wanted to prevent China from making revolution, saying that we should not have a civil war and should cooperate with Chiang Kai-shek, otherwise the Chinese nation would perish. But we did not do what he said. The revolution was victorious. After the victory of the revolution he [Stalin] next suspected China of being a Yugoslavia, and that I would become a second Tito. | „ |

That account of Stalin’s attitude is substantiated by a whole series of public gestures at the time, culminating in the fact that, when the People’s Liberation Army (successor to the Red Army) took the Nationalist capital of Nanjing in April 1949, the Soviet ambassador was the only foreign diplomat to accompany the retreating Nationalist government to Guangzhou. Stalin’s motives were obviously those described by Mao in the above passage; he did not believe in the capacity of the Chinese communists to achieve a clear-cut victory, and he thought they would be a nuisance if they did.

Formation Of The People’s Republic Of China edit

Nevertheless, when the communists did take power in China, both Mao and Stalin had to make the best of the situation. In December 1949 Mao, now chairman of the People’s Republic of China—which he had proclaimed on October 1—traveled to Moscow, where, after two months of arduous negotiations, he succeeded in persuading Stalin to sign a treaty of mutual assistance accompanied by limited economic aid. Before the Chinese had time to profit from the resources made available for economic development, however, they found themselves dragged into the Korean War in support of Kim Il-sung's Moscow-oriented regime in North Korea. Only after that baptism of fire did Stalin, according to Mao, begin to have confidence in him and believe he was not first and foremost a Chinese nationalist.

Despite those tensions with Moscow, the policies of the People’s Republic of China in its early years were in very many respects based, as Mao later said, on “copying from the Soviets.” While Mao and his comrades had experience in guerrilla warfare, in mobilization of the peasants in the countryside, and in political administration at the grass roots, they had no firsthand knowledge of running a state or of large-scale economic development. In such circumstances the Soviet Union provided the only available model. A five-year plan was therefore drawn up under Soviet guidance; it was put into effect in 1953 and included Soviet technical assistance and a number of complete industrial plants. Yet, within two years, Mao had taken steps that were to lead to the breakdown of the political and ideological alliance with Moscow.

The Emergence Of Mao’s Road To Socialism edit

In the spring of 1949, Mao proclaimed that, while in the past the Chinese revolution had followed the unorthodox path of “encircling the cities from the countryside,” it would in the future take the orthodox road of the cities leading and guiding the countryside. In harmony with that view, he had agreed in 1950 with Liu Shaoqi that collectivization would be possible only when China’s heavy industry had provided the necessary equipment for mechanization. In a report of July 1955, he reversed that position, arguing that in China the social transformation could run ahead of the technical transformation. Deeply impressed by the achievements of certain cooperatives that claimed to have radically improved their material conditions without any outside assistance, he came to believe in the limitless capacity of the Chinese people, especially of the rural masses, to transform at will both nature and their own social relations when mobilized for revolutionary goals. Those in the leadership who did not share that vision he denounced as “old women with bound feet.” He made those criticisms before an ad hoc gathering of provincial and local party secretaries, thus creating a groundswell of enthusiasm for rapid collectivization such that all those in the leadership who had expressed doubts about Mao’s ideas were soon presented with a fait accompli. The tendency thus manifested to pursue his own ends outside the collective decision-making processes of the party was to continue and to be accentuated.

Even before Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev, had given his secret speech (February 1956) denouncing his predecessor’s crimes, Mao Zedong and his colleagues had been discussing measures for improving the morale of the intellectuals in order to secure their willing participation in building a new China. At the end of April, Mao proclaimed the policy of “letting a hundred flowers bloom”—that is, the freedom to express many diverse ideas—designed to prevent the development in China of a repressive political climate analogous to that in the Soviet Union under Stalin. In the face of the disorders called forth by de-Stalinization in Poland and Hungary, Mao did not retreat but rather pressed boldly forward with that policy, against the advice of many of his senior colleagues, in the belief that the contradictions that still existed in Chinese society were mainly nonantagonistic. When the resulting “great blooming and contending” got out of hand and called into question the axiom of party rule, Mao savagely turned against the educated elite, which he felt had betrayed his confidence. Henceforth he would rely primarily on the creativity of the rank and file as the agent of modernization. As for the specialists, if they were not yet sufficiently “red,” he would remold them by sending them to work in the countryside.

It was against that background that Mao, during the winter of 1957–58, worked out the policies that were to characterize the Great Leap Forward, formally launched in May 1958. While his economic strategy was by no means so one-sided and simplistic as was commonly believed in the 1960s and ’70s and although he still proclaimed industrialization and a “technical revolution” as his goals, Mao displayed continuing anxiety regarding the corrupting influence of the fruits of technical progress and an acute nostalgia for the perceived purity and egalitarianism that had marked the moral and political world of the Jinggang Mountains and Yan’an eras.

Thus it was logical that he should endorse and promote the establishment of “people’s communes” as part of the Great Leap strategy. As a result, the peasants, who had been organized into cooperatives in 1955–56 and then into fully socialist collectives in 1956–57, found their world turned upside down once again in 1958. Neither the resources nor the administrative experience necessary to operate such enormous new social units of several thousand households were in fact available, and, not surprisingly, the consequences of those changes were chaosand economic disaster.