1967 Detroit riots

| “ | Black day in July The streets of Motor City are now are quiet and serene. But the shapes of gutted buildings strike terror to the heart. And you say, 'how did it happen'? And you say, 'how did it start'? Why can't we all be brothers? Why can't we live in peace? But the hands of the have-nots Keep falling out of reach. |

„ |

| ~ Gordon Lightfoot, "Black Day in July" |

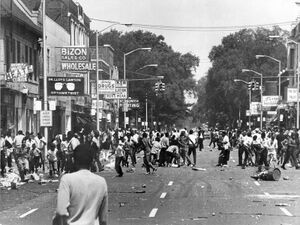

The 1967 Detroit riots, also known as the Detroit Rebellion and the 12th Street Riot, was the bloodiest incident in the "Long, hot summer of 1967". Composed mainly of confrontations between black residents and the Detroit Police Department, it began in the early morning hours of Sunday July 23, 1967, in Detroit, Michigan.

The precipitating event was a police raid of an unlicensed, after-hours bar, then known as a "blind pig", on the city's Near West Side. It exploded into one of the deadliest and most destructive riots in American history, lasting five days and surpassing the scale of Detroit's 1943 race riot 24 years earlier.

Governor George W. Romney ordered the Michigan Army National Guard into Detroit to help end the disturbance. President Lyndon B. Johnson sent in the United States Army's 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions. The result was 43 dead, 1,189 injured, over 7,200 arrests, and more than 400 buildings destroyed.

The scale of the riot was the worst in the United States since the 1863 New York City draft riots during the American Civil War, and it was not surpassed until the 1992 Los Angeles riots 25 years later.

Background[edit]

In the sweltering summer of 1967, Detroit’s predominantly African American neighborhood of Virginia Park was a simmering cauldron of racial tension. About 60,000 low-income residents were crammed into the neighborhood’s 460 acres, living mostly in small, sub-divided apartments.

The Detroit Police Department, which had only about 50 African American officers at the time, was viewed as a white occupying army. Accusations of racial profiling and police brutality were commonplace among Detroit’s Black residents. The only other whites in Virginia Park commuted in from the suburbs to run the businesses on 12th Street, then commuted home to affluent enclaves outside Detroit.

The entire city was in a state of economic and social strife: As the Motor City’s famed automobile industry shed jobs and moved out of the city center, freeways and suburban amenities beckoned middle-class residents away, which further gutted Detroit’s vitality and left behind vacant storefronts, widespread unemployment and impoverished despair.

A similar scenario played out in metropolitan areas across America, where “white flight” reduced the tax base in formerly prosperous cities, causing urban blight, poverty and racial discord. In mid-July, 1967, the city of Newark, New Jersey, erupted in violence as Black residents battled police following the beating of a Black taxi driver, leaving 26 people dead.

At night, 12th Street in Detroit was a hotspot of inner-city nightlife, both legal and illegal. At the corner of 12th St. and Clairmount, William Scott operated a “blind pig” (an illegal after-hours club) on weekends out of the office of the United Community League for Civic Action, a civil rights group. The police vice squad often raided establishments like this on 12th St., and at 3:35 a.m. on Sunday morning, July 23, they moved against Scott’s club.

On that warm, humid night, the establishment was hosting a party for several veterans, including two servicemen recently returned from the Vietnam War, and the bar’s patrons were reluctant to leave the air-conditioned club. Out in the street, a crowd began to gather as police waited for vehicles to take the 85 patrons away.

An hour passed before the last person was taken away, and by then about 200 onlookers lined the street. A bottle crashed into the street. The remaining police ignored it, but then more bottles were thrown, including one through the window of a patrol car. The police fled as a small riot erupted. Within an hour, thousands of people had spilled out onto the street from nearby buildings.

Looting began on 12th Street, and closed shops and businesses were ransacked. Around 6:30 a.m., the first fire broke out, and soon much of the street was ablaze. By midmorning, every policeman and fireman in Detroit was called to duty. On 12th Street, officers fought to control the unruly mob. Firemen were attacked as they tried to battle the flames.

Detroit Mayor Jerome P. Cavanaugh asked Michigan Governor George Romney to send in the state police, but these 300 additional officers could not keep the riot from spreading to a 100-block area around Virginia Park. The National Guard was called in shortly after but didn’t arrive until evening. By the end of Sunday, more than 1,000 people were arrested, but the riot kept spreading and intensifying. Five people had died by Sunday night.

On Monday, the rioting continued and 16 people were killed, most by police or guardsmen. Snipers reportedly fired at firemen, and fire hoses were cut. Governor Romney asked President Lyndon B. Johnson to send in U.S. troops. Nearly 2,000 army paratroopers arrived on Tuesday and began patrolling the streets of Detroit in tanks and armored carriers.

Ten more people died that day, and 12 more on Wednesday. On Thursday, July 27, order was finally restored. More than 7,000 people were arrested during the four days of rioting. A total of 43 people were killed. Some 1,700 stores were looted and nearly 1,400 buildings burned, causing roughly $50 million in property damage. Some 5,000 people were left homeless.

The so-called 12th Street Riot was considered one of the worst riots in U.S. history, occurring during a period of fever-pitch racial strife and numerous race riots across America.